This convenience comes at a cost, however, and experts warn that plastics’ inability to biodegrade is taking a toll on the planet. To make matters worse, recycling infrastructure around the world is severely underdeveloped. In this infographic from Swissquote, we recount the end of “easy” recycling, and examine the struggles that many countries are facing as they scale up their domestic capabilities.

The Single-Supplier Global Recycling Model

Since the early 1990s, developed countries have avoided the environmental costs of plastic by outsourcing their recycling to the developing world—more specifically, China. At the time, this arrangement benefited both parties. On one hand, it was cheaper for developed countries to export their plastic waste rather than process it domestically. China, on the other hand, needed vast amounts of raw materials to fuel its burgeoning manufacturing industries. It also meant that Chinese container ships, which regularly delivered goods to countries like the U.S., would no longer return home empty-handed. A system that relies heavily on one country can only handle so much, however, and by 2016 China was importing 7 million tonnes of recyclables and waste per year. To make matters worse, plastics production kept growing at a faster rate than the global population: Source: PlasticsEurope, Worldometer It was clear that this system would soon reach its tipping point, especially with the Chinese government largely committed to going green.

National Sword Policy

China’s solution to cutting down plastic imports was the National Sword policy, which at the start of 2018, implemented an import ban on 24 types of recyclables. The ban was extremely effective—plastic exports to China fell from 581,000 tonnes in February of 2017 to just 23,900 tonnes a year later. All of this plastic did not simply disappear, though. Plastic-exporting countries scrambled for alternatives, and in some cases, diverted their shipments to nearby countries in Southeast Asia. Governments in the region were quick to respond, either refusing shipments or implementing bans of their own. —Lea Guerrero, Greenpeace Philippines In one noteworthy case, Rodrigo Duterte, President of the Philippines, threatened to wage war on Canada if it did not take back its shipments of waste. An official later clarified this threat was not to be taken literally.

The End of “Easy” Recycling

Western countries tend to produce more plastics per capita than other countries, but are ill-prepared to begin processing their own plastic waste in a sustainable manner. One critical issue arises from their predominant method of recycling known as single-stream recycling. Under this method, consumers place all of their recyclables into a single bin. This mixture of cardboard, plastics, and glass is then brought to a material recovery facility (MRF) to be sorted and processed. While this method makes it easier for consumers to recycle, it suffers from two weaknesses: With outsourcing no longer an option, MRFs across the U.S. are now dealing with significantly larger volumes. To boost their capacity, some facilities have implemented artificial intelligence (AI) empowered robots that can sort items significantly faster than humans. An added bonus to reducing the human workforce is safety—MRFs frequently have some of the industry’s highest injury and illness incidence rates.

Investing in Domestic Solutions

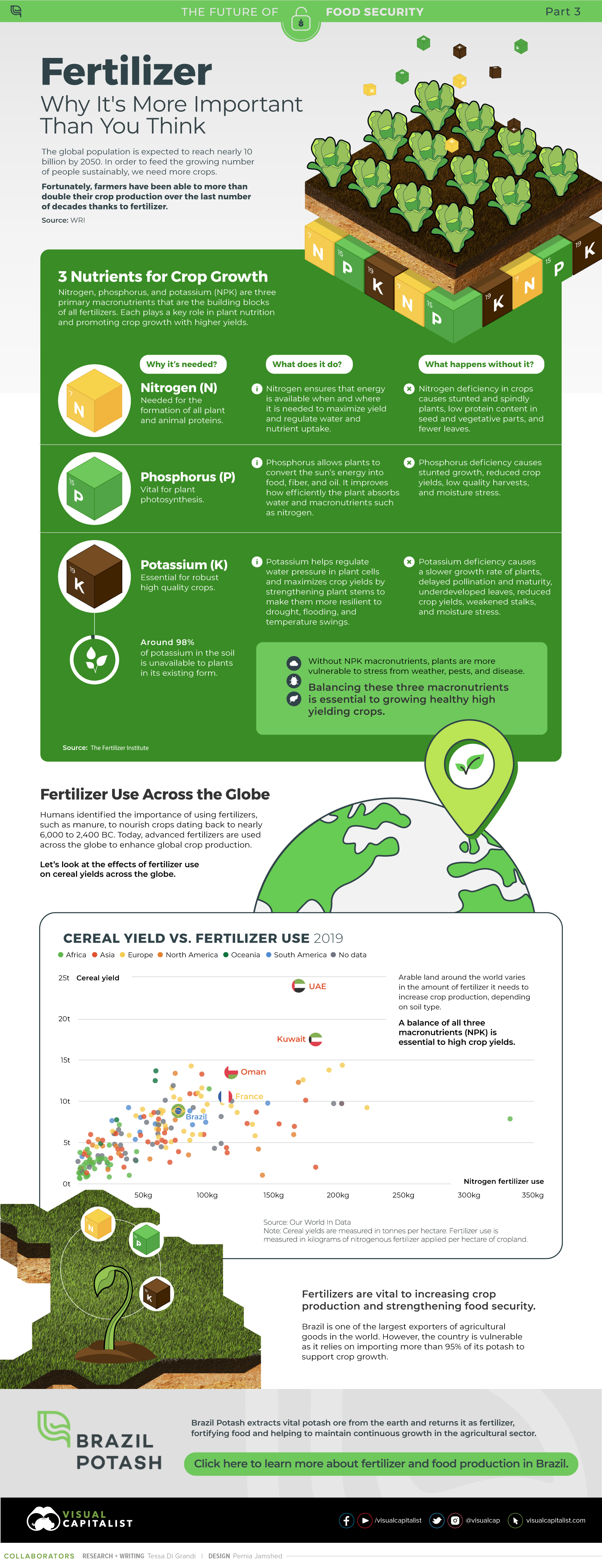

China’s ban on foreign plastics has exposed the frailty of a single-supplier global recycling model, and is forcing many countries to begin developing their domestic infrastructure. One emerging leader in this space is the EU, which has passed ambitious legislation to promote recycling industry investment. Recognizing the unsustainability of single-use plastics, the EU has mandated its member states to achieve a 90% collection rate for plastic bottles by 2029. It’s also set a target for all plastic packaging to be recyclable or reusable by 2030, an initiative that could create up to 200,000 new jobs. Aside from the environmental benefits, the global recycling industry could also be a source of economic growth. It’s estimated that between 2018 and 2024 that it will grow at a CAGR of 8.6% to reach $63 billion. on Over recent decades, farmers have been able to more than double their production of crops thanks to fertilizers and the vital nutrients they contain. When crops are harvested, the essential nutrients are taken away with them to the dining table, resulting in the depletion of these nutrients in the soil. To replenish these nutrients, fertilizers are needed, and the cycle continues. The above infographic by Brazil Potash shows the role that each macronutrient plays in growing healthy, high-yielding crops.

Food for Growth

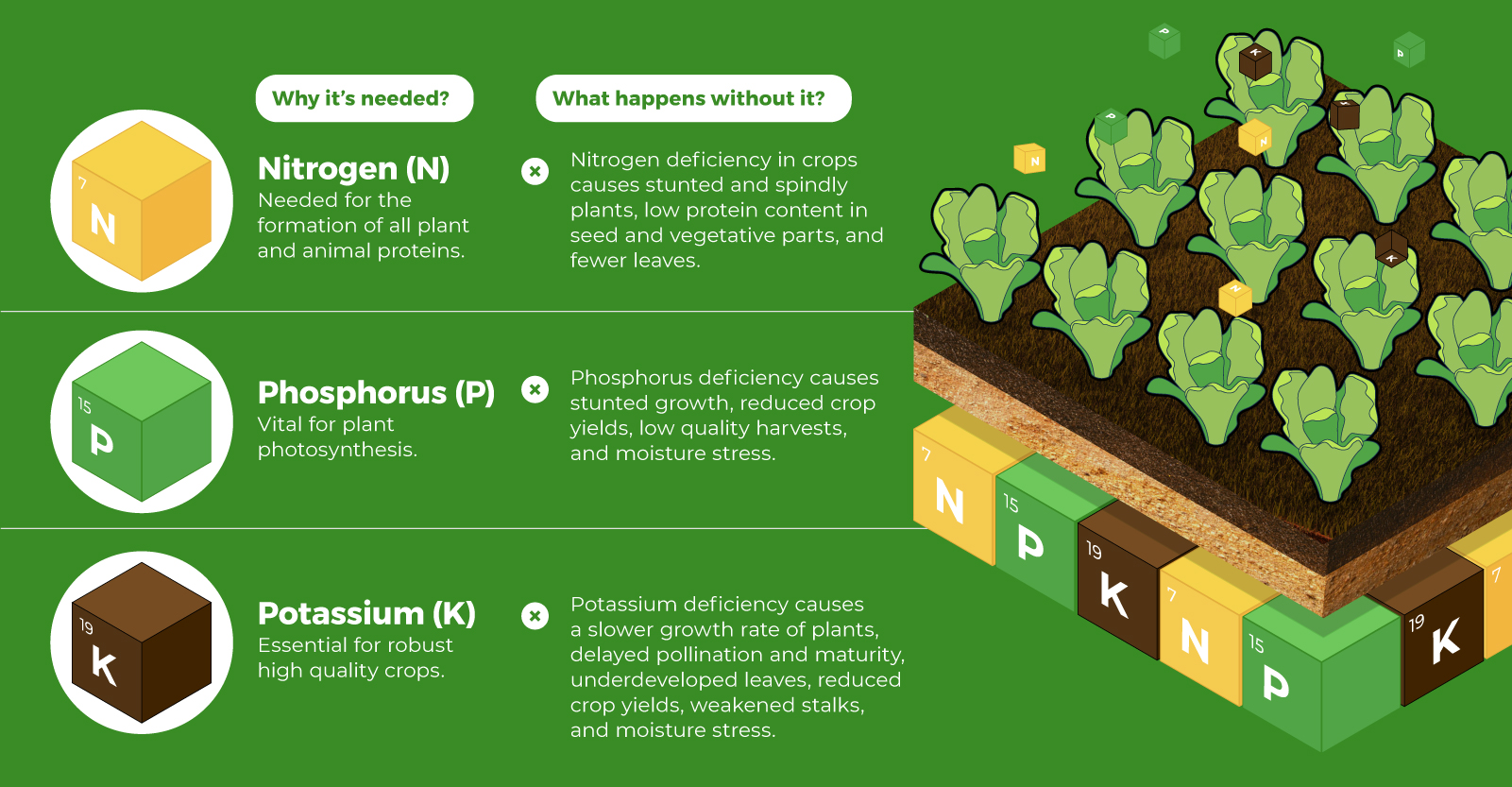

Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) are three primary macronutrients that are the building blocks of the global fertilizer industry. Each plays a key role in plant nutrition and promoting crop growth with higher yields. Let’s take a look at how each macronutrient affects plant growth. If crops lack NPK macronutrients, they become vulnerable to various stresses caused by weather conditions, pests, and diseases. Therefore, it is crucial to maintain a balance of all three macronutrients for the production of healthy, high-yielding crops.

The Importance of Fertilizers

Humans identified the importance of using fertilizers, such as manure, to nourish crops dating back to nearly 6,000 to 2,400 BC. As agriculture became more intensive and large-scale, farmers began to experiment with different types of fertilizers. Today advanced chemical fertilizers are used across the globe to enhance global crop production. There are a myriad of factors that affect soil type, and so the farmable land must have a healthy balance of all three macronutrients to support high-yielding, healthy crops. Consequently, arable land around the world varies in the amount and type of fertilizer it needs. Fertilizers play an integral role in strengthening food security, and a supply of locally available fertilizer is needed in supporting global food systems in an ever-growing world. Brazil is one of the largest exporters of agricultural goods in the world. However, the country is vulnerable as it relies on importing more than 95% of its potash to support crop growth. Brazil Potash is developing a new potash project in Brazil to ensure a stable domestic source of this nutrient-rich fertilizer critical for global food security. Click here to learn more about fertilizer and food production in Brazil.